Hi friends,

At the end of this email is a very short survey about writers’ circles! If you find your eyes crossing mid-way through my meanderings, feel free to scroll on down and click on the link! You’re the best!

One painful winter in preschool, my son got three concussions in six weeks: a classmate named Alex whacked him on his head with a block, and then he slipped on some black ice and fell backwards whilst breakdancing, and then he was jamming out in the shower and headbanged into the water fixture. We were very lucky to have a pediatrician with a sense of humor.

Fast forward eight years to this morning, when I read this article about how Miami is integrating AI into every classroom. I texted my husband: "if NYC does this, we’re homeschooling.” Miami isn’t alone, but the article compounded my overwhelming fear that we are in the process of headbanging and breakdancing our intelligence away. We don’t need little Alex to thwack us—we’re doing it ourselves.

Those of you who have been around for a while have followed my transformation from dabbler to luddite as I’ve tried to figure out this bold new world of ChatGPT and its ilk. This is my latest installment of how I’m thinking about the impact of generative AI on the things I love most: reading and writing and learning and thinking.

I know it’s the end of the semester for a lot of people and we’re all burned out and so this might feel like I’m preaching to a very exhausted choir. If that’s the case, go get a fun iced drink, read a novel outside somewhere, and read this in the fall.

Is Literacy Part of What Makes Us Human?

A few years ago, I read Marina Umaschi Bers’s Beyond Coding, and I was struck by the beauty behind the book’s argument. She argues that coding is an essential form of literacy that enables creativity, critical thinking, and can ultimately make us more human. In the examples she uses from schools, coding encourages students to be playful. Experimental. Engaged.

Since then, I’ve been mulling over this connection between literacy and becoming more human. Kenneth Burke roots humanity in our manipulation of symbols: for him, humans are “the symbol-using (symbol-making, symbol-misusing) animal” and the “inventor of the negative.”

As I wrote about a few weeks ago, writing and reading are the hardest of the word-based skills to master because they are the ones we taught ourselves (whereas we’re born hard-wired to speak and listen). Language itself, as philosophers and linguists insist, is this essential part of our humanity.

Neoliberalism blah blah blah

The problem in all of this, of course, is that no one has time. We have too many students, too many preps, a CV that would have gotten you tenured in the nineties won’t get you an interview today. And of course, AI promises to be the silver bullet that solves these problems.

I won’t tell you I never use it—after I saw a demonstration of MagicSchool, I told my mom, a retired second-grade teacher turned amazing semi-retired tutor, that she should check it out. My husband was having a problem with a graphic design program this weekend, the FAQ and forums were no help, and ChatGPT solved the problem for him in two minutes. Even though I know and love a good thesaurus, it sometimes helps me figure out a stream-of-consciousness synonym for words on the tip of my tongue (“I’m trying to find a word to describe a world leader that is like incompetent, but also a hint of embarrassing…but the world leader doesn’t know it’s embarrassing…” AI: “Is cringingly inept too colorful?”) I also know that AI has been a gamechanger for neurodiverse friends of mine who use it as a way to externalize some organization and accountability. And its capacity to automate tasks like data analysis is huge. I know, I know.

In these cases, I have the sense that AI is doing what tools should do: it is acting as a tool so that experts can lean into their expertise. My mom shouldn’t have to spend her time writing 40 story problems—her time is better spent picking the 10 best ones, and figuring out how to teach them. If AI could actually do citations properly, that would be a gamechanger, freeing academics up for things that need our particular energy. We don’t need to transcribe old documents if AI can do it for us.

But.

Education, scholarship, what’s the point?

Here’s my argument: if something needs your particular energy and expertise, don’t outsource it. If something is meant to develop a skill or expertise, don’t outsource it.

When you look at that NYT article about the Miami schools, all of the examples are smoke and mirrors—or outsourcing of something we should own (like providing feedback on essays). Being able to talk to a clunky AI chatbot of JFK and calling that progress reminds me of when my classroom got a laser disc player in fourth grade. Where is the skill? Where is the wonder? How is a JFK chatbot more useful to students than studying his speeches? The frantic promotion around AI—the solution in search of a problem—just reminds me so much of Mad Men (create the problem, sell the solution). “Kids will NEED these skills!” “What skills is this teaching? And what skills are they losing?” “AI SKILLS.” Ah okay. (Also, the kids with AI skills aren’t getting jobs! It’s the art historians! This is delightful).

But—and we all know this—academics are getting AI to write drafts of papers, reviewers are feeding those drafts of papers back into AI to generate reviews (not cool, friends! Don’t use AI to write your reviews! Peer review belongs to us!), and then students are using AI to write summaries—of papers that were written then reviewed by AI to begin with.

A lot of calls for editors show up in my inbox, and I’ve seen two in the past week from authors who say they had AI write the first draft of something, and now they want an editor to make it sound like “it was written in an authentic human voice.” Of course, this model forgoes authenticity at both the drafting and editing stages, so this feels unlikely.

This is how we give ourselves a concussion.

The process is the point

The problem is, as scholars and educators, we need to start—and encourage our students to start—with messy, imprecise thoughts, and then work to develop them into something cool. So much research is contextual, contingent, accidental.

I’ve also spent time looking at AI-generated feedback that programs give students, and it’s…not good! I worry that we’re about to teach a whole generation of kids how not to think (and yes I know people said that about radios and TVs and computers and spell check and calculators).

My sense is that we’re losing sight of something important about process, about formative stages. As scholars, the goal isn’t just to generate a published paper or book. It’s to learn something new about the world, and to make a case for how that knowledge makes us a little more human, and to put that in conversation with people who are asking similar questions. AI isn’t curious, so it can’t do that. AI isn’t literate, so it can’t usefully critique ideas. When I read Lab Girl, I was struck most by how shoe string the most fun parts of her scientific career are. The provenance of accident.

For a lot of what we do output isn’t the point—the process is. Our role in designing our own courses and writing our own lectures and doing our own research and—yes—writing our own reviews and doing our own grading matters. The point is the slow part. And we all have a role in this—we can hire people with fewer, but better publications. We can assign our students less, but more meaningful, work. We can show that reading entire texts can be worth it. We can make ourselves more literate, instead of just more productive. We can grade on process, not just product.

One last thought—these people are the bad guys

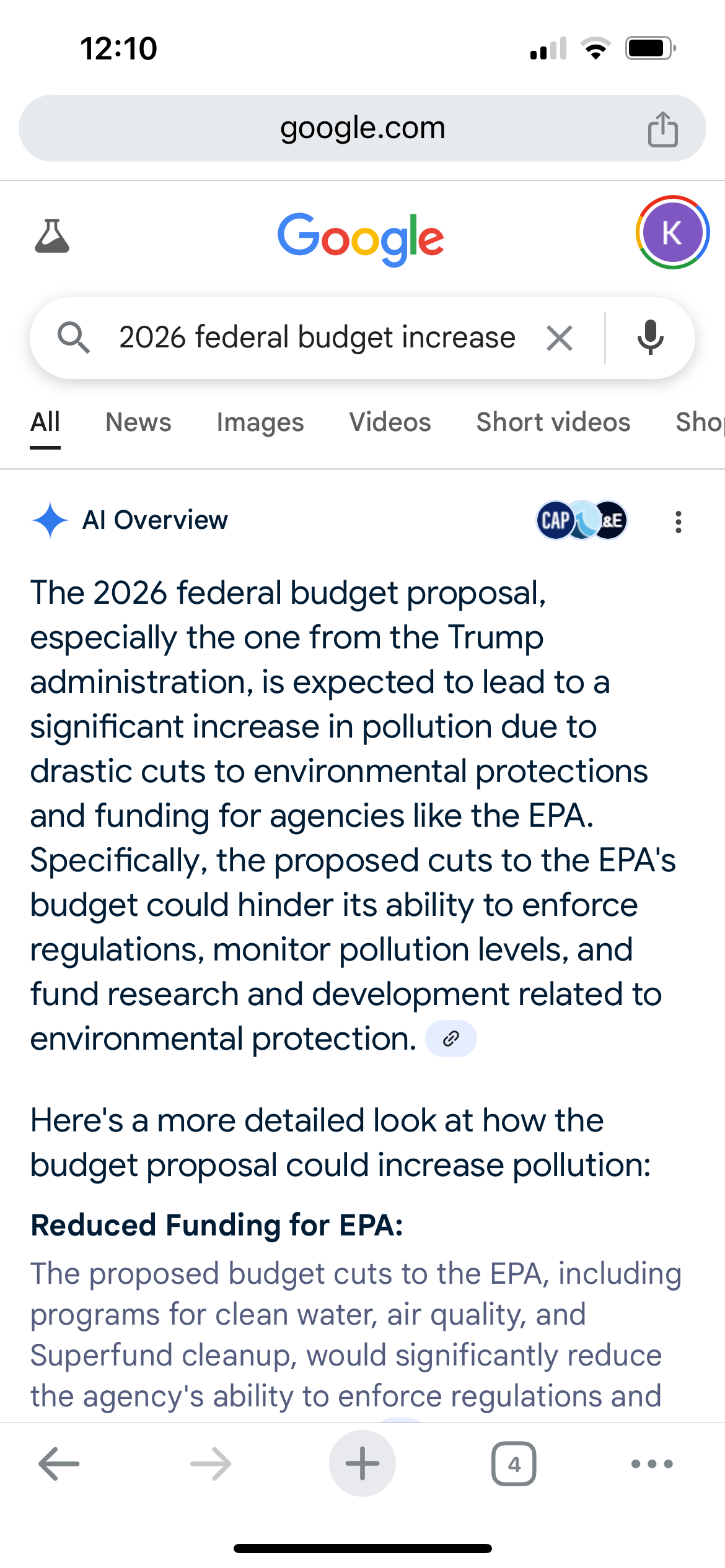

Obviously we want knowledge to be true, but we also want it to be free. This feels like a core aspect of acquiring literacy as a citizen. I remember being so surprised when I learned about the Chinese censorship of terms related to Tiananmen Square. However, we know that AI generators are doing the same thing. You only have to follow the unhinged story about Grok being hard coded to acknowledge white genocide (and then expressing skepticism about the Holocaust! Oops!) Or the fact that when you ask Google about the 2026 federal budget and pollution, it tells you:

but when you add Trump into the string it says:

These are political actors who bend to fascist winds, and should not be given the privilege of shaping the future of scholarship or education.

And on that happy note, closing my computer now!

xoxo

Kelly

Four small post-scripts—

**The fun essay I told you about last time? It got rejected again! Whee! One day it will find a home, right?

**People have been asking if there will be a writers’ circle in the fall. OF COURSE! Wouldn’t miss it. I’ll have more information in June, but if you’re interested in them and could fill out this brief survey, that would be amazing.

**I won’t be around next week, so the next time I write to you will in in JUNE.

**I don’t have this as an official service yet, but lately I’ve gotten to do interview coaching for executive-level positions (inside and outside of academia) with some existing clients and it’s been really fun! And they’ve been really successful! (Because they’re brilliant—I just nudge them to communicate their brilliance). Anyway, if you have a job interview coming up and need someone to help, let’s chat.